So, that evening here (4:30 AM, London time, there), Dominic Laurie, a Business Presenter for BBC, called me with questions circling news that Guy Laliberte is now offering 90% of his ownership to outside investors, causing Canadians to fear that he is about to desert them. Here is what I tossed Laurie's way -- not exactly in these words:

In the beginning, CDS produced an infallible magic that lasted for years. They could do no wrong, and then, the world changed, as always it does. Laliberte could not control his lust for spreading out into more venues, inking contracts for 10-year runs from one city after another, New York to LA, and over in China and elsewhere. Reckless confidence.

The contracts lined up like doomed dominoes, and, likewise, soon came cascading down into an embarrassing heap of fiascoes, one after another, four or five in a row. The product was getting denigrated in over-expansion, over-saturation.

The Cirque King’s most strategic blunder: Not closing his vaudeville stage show, Banana Shpeel, out of town in Chicago, where it had reaped critical and consumer disdain, but stubbornly pushing it onto New Yorkers. All of which marked Cirque in Big Apple eyes as just another desperate player wanting to take Broadway on a lark.

That old infallible magic was beginning to fade. Other denigrations to the product: Throwing shows originally presented under enchanted tents, into large humdrum arenas, making them look and sound more common. Desperation invaded the box office. The product was being diluted. Don’t like those words "product" and "diluted," but they fit.

What about the Canadian government? That’s what Laurie most wanted to talk about Sure. In essence, Canadian taxpayers funded Cirque in the begriming, about up to a million and a half, giving the show so many years to make it on its own. Great smart idea, I told Laurie. In around five seasons, Cirque du Soleil had weened itself off the subsidies.

Here’s where a budding morality play gains traction: Given that, minus government start-up money, it's doubtful there would have ever been a Cirque du Soleil as we know it, does Laliberte bear a moral obligation to keep the headquarters in Montreal? A lot of people up there, fearing the worst as Mr. Circus goes looking for buyers, believe he does, even though he, or those who buy him out, can go wherever they want, Nepal to New Jersey.

Big sigh on my end. Pressing myself to a point, I talked about Steve Jobs, who had groomed Tim Cook to take over Apple. And I implied that I don’t think Laliberte has ever done such a thing. I mentioned Kenneth Feld grooming his three daughters to take over as Ringling producers.

That's about the gist of it, dressed up rhetorically for this post.

So, one of the greatest circus impresarios who ever lived seems very alone in his ominously shrinking kingdom. Some prospective investors last year pulled out when, given access to the books, they came upon unsettling evidence of a disintegrating balance sheet.

You can’t get much more than that in ten minutes, though I did, tracing Cirque's artistic roots back to the Russians -- in reply to Laurie's wanting to know what made the Cirque version of circus so special. Okay. There it was. It was fun, walking a rhetorical high wire to a drum beat incessantly pushing for a shorter act. Being grilled by, of all mortals, a business reporter!

I wonder if my voice even went out over UK airwaves.

Update, 3/31/15: It did! A tad scratchy, but I was pleased with two of the points I made that got quoted -- about Cirque's rapid rise on the world stage after the 1987 L.A. date, and how intelligently the Canadian govt had funded them in the beginning -- giving them so many years to make it on their own before the funding would end.

BTW: The BBC World Service, I've just discovered, reaches the largest broadcast audience in the world, about 200 million people a week, and in 28 languages.

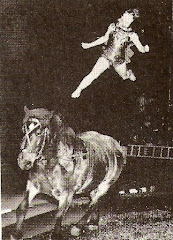

The most thrilling moment in Los Angeles. 1987: this one act, by Amelie Demaiy and Eric Varelas, seductively scored to a tango, sensually choreographed straight through, not a breech in the fabric, brought down the house and sealed the show's fate in LA. Overnight, Cirque du Soleil's acclaim skyrocketed from local to global.

All photos, from the 1987 program magazine for the Los Angeles Arts Festival run:

* Guy Laliberte, left, with his first artistic director, Guy Caron

* The tent that went to Los Angeles.

* Some of the company members

* Progaram magazine message of good will from one of many government sponsors, Benoit Bouchard, Minister of Employment and Immigration

* The penguin-businessmen tetterboard act

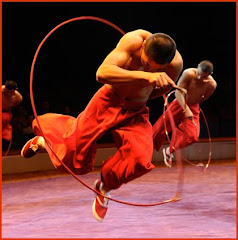

* Chinese Trick-Cycling riders from Beijing

* Demay and Varelas

************************************************

Next stop on this thread: My interview, six years back, for Phil Weyland’s documentary on Miguel Vazquez, The Last Flyer, to be uncorked down in Sarasota, come April.

From a welcome message from Phil, seems I escaped the cutting room floor. I have a few cameos in the film. Tell you more about it soon.